- Georgia Biodiversity Portal: Freshwater Mollusks

- What are Freshwater Mussels?

- Georgia’s Native Freshwater Mussel Fauna

- Biology & Ecology of Freshwater Mussels

- Conservation of Freshwater Mussels

- Freshwater Mussel Identification

- More About Mussels in Georgia

- Glossary of Terms

What are Freshwater Mussels?

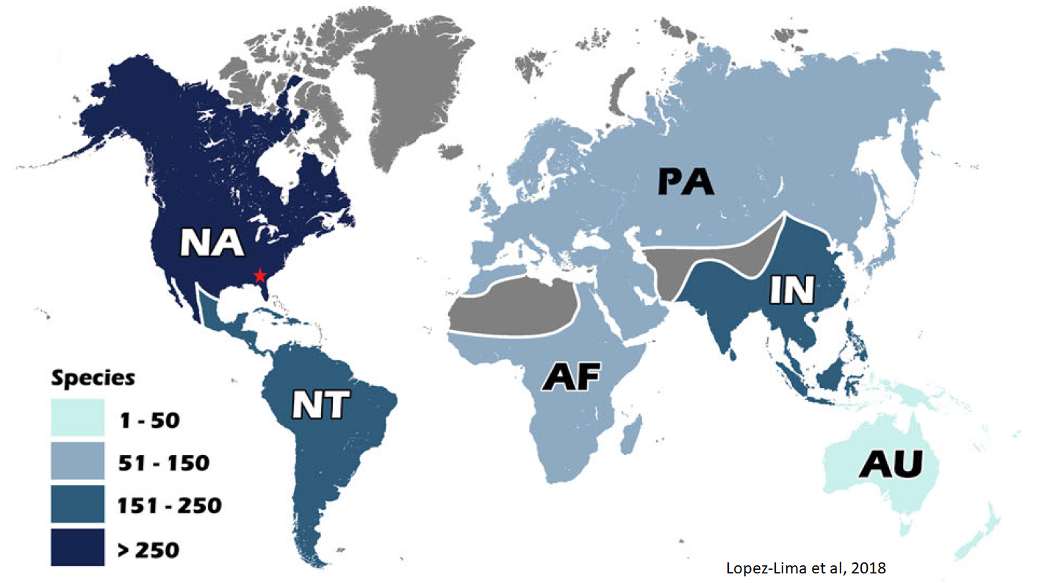

Freshwater mussels are found on all continents except Antarctica and inhabit rivers, streams, and lakes. There are roughly 1000 species of these mussels worldwide with North America being home to around 300 species. North America's native freshwater mussels, also referred to as “Pearly Mussels” or “Unionids”, are a diverse group of bivalves (two-shelled) mollusks in the Order Unionida. They, like their marine ancestors, are infaunal (live buried in the bottom) filter feeders and live largely sedentary lives filtering particles of algae, plankton, detritus, and bacteria out of the water.

Zoogeographic regions are:

NA = Nearctic

NT = Neotropical

PA = Palearctic

AF = Afrotropical

IN = Indotropical

AU = Australasian

Georgia’s Native Freshwater Mussel Fauna

Georgia boasts one of the most diverse freshwater mussel faunas in the world and is home to over 120 species—over 10% of all freshwater mussel species worldwide. Freshwater mussels are divided into two families in North America: Margaritiferidae and Unionidae. Unionidae is comprised of 55 recognized genera, 34 of which have species representatives in Georgia; whereas Margaritiferidae is comprised of just two genera and six species, none of which are known from Georgia waters.

The State of Georgia encompasses a wide variety of geologic features resulting in a diverse assortment of habitats. Eleven major river basins flow across Georgia radiating out into the Atlantic, Eastern Gulf of Mexico, and Interior drainages (e.g., Tennessee River). This habitat complexity, combined with a warm climate and other factors, has resulted in a rich diversity of native aquatic wildlife.

Freshwater Mussel Species Diversity by River Basin

Coosa

41

6

2

Tennessee

39

4

1

Apalachicola

Chattahoochee

Flint

31

30

28

3

-

-

2

-

-

Savannah

25

-

-

Ochlockonee

23

2

1

Altamaha

Ocmulgee

Oconee

20

17

16

-

-

-

-

-

-

Ogeechee

18

-

-

Suwannee

Withlacoochee

15

15

1

-

-

-

St. Marys

9

-

-

Tallapoosa

7

-

-

Satilla

3

-

-

Total Recognized Species

126

15

6

Table: Diversity of freshwater mussel species in major Georgia River basins and river systems. Italicized names are sub-basins within the parent basin.

- “Species in Georgia” represents an approximate total number of recognized species within each basin known to have naturally occurred in Georgia.

- “Species Lost from Georgia” represents species which are no longer believed to occur within the borders of Georgia, including those which are extinct and those that still occur elsewhere outside of Georgia.

- “Extinct Species” represents species which are globally extinct.

- “Total Recognized Species” is the total number of unique species present within the state. Species occurring in multiple basins are only represented once in these values.

Freshwater mussel science is progressing rapidly, and these figures are subject to change and interpretation as our knowledge of mussels increases.

Examples of Georgia Mussel Species

Fun Fact: Current research points to this species only using fish from the sucker family, such as Jumprocks and Redhorses, as hosts. Metamorphosis rates were low, however, so the primary host for this species may still be a mystery.

Fun Fact: This species, one of only two Amblema species in Georgia and three in the world, is listed as federally endangered. While present below Seminole Reservoir in Florida, E. neislerii was thought lost from Georgia in its native range in the Flint River for almost 16 years until a few individuals were found at a location in the Flint in 2007. It remains very rare in GA but appears to have benefited from the secession of dredging in the Apalachicola River, Florida in 2001.

Fun Fact: Mussels from the genus Cyclonaias are thick shelled and often covered in intricate patterns of bumps and ridges. Members of this genus usually specialize in catfish as their fish hosts.

Fun Fact: This species is endemic to the Altamaha River basin in Georgia and is one of only three species in North America to produce spines. It is believed that the spines allow the mussel to stabilize itself in loose sandy conditions. E. spinosa is one of the rarest mussels in Georgia and occurs nowhere else in the world.

Fun Fact: This species went undetected for over half a century until a specimen was found in Baker County, GA in 2000. Extensive survey efforts have since located more individuals and populations in the Flint River.

Fun Fact: The genus Elliptio is the most speciose (richness of species) and abundant genus in North America and can take a wide variety of forms from the thick and stumpy Elephantear (E. crassidens) in the Flint River, to the slender spike-like Altamaha Lance (E. shepardiana) in the Altamaha River.

Fun Fact: This species produces a single large fish-like superconglutinate, complete with a lateral line and eye spot, which it extends on a long mucus thread. The superconglutinate moves in the current and entices predatory fish to take a bite.

Fun Fact: This species, like many members of it’s genus, has a long flowing mantle lure that resembles a small fish. The mussel pulses this lure to entice large predator fish to strike.

Fun Fact: Georgia is home to all six species of the small enigmatic mussels in the genus Medionidus. Five of the six species are listed as Threatened or Endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The Suwannee Moccasinshell (M. walkeri) The Ochlockonee Moccasinshell (M. simpsonianus), were even thought to be extinct before being rediscovered in 2014 and 2015!

Fun Fact: This species is the only member of the genus Megalonaias and are one of the largest freshwater mussels in the world, reaching up to nearly 12 inches and several pounds. This species was popular for making pearl buttons before the invention of plastics.

Fun Fact: Mussels from this genus use minnows as their hosts and produce tiny free-floating conglutinates that resemble small invertebrates and stimulate drift-feeding minnows to strike.

Fun Fact: Mussels from the genus Pyganodon specialize in soft, muddy areas with slowly moving water. Their thin, light shells give them an advantage in these silty habitats.

Fun Fact: Mussels from the genus Uniomerus are experts at living in small streams. They can burrow to weather long periods of drought lasting months!

Fun Fact: Females from this genus can be differentiated from their male counterparts by the shape of their shells which broaden at the posterior end to make room for brooding larvae.

Fun Fact: This species climbs all the way out of the sand and lies on its side to display its large, showy lure which is thought to mimic a crayfish or hellgrammite to attract their large predator host fish.

Biology & Ecology of Freshwater Mussels

One important area where freshwater mussels differ from their far more numerous marine (saltwater) bivalve cousins is in their unique and fascinating reproductive strategies. In marine environments, bivalves release planktonic larvae which drift with ocean currents before settling and growing into adults. Mussels which have evolved in flowing river systems would only have their offspring washed downstream if they were to utilize this strategy. In order to overcome this obstacle and increase their dispersal options, freshwater mussels have adapted an ingenious strategy: they hitch a ride.

All ~1000 species of unionids on Earth are parasitic and use the gills, fins, and skin of fish to protect and disperse their tiny, Pac-Man-like larvae known as “glochidia”. In order to achieve this feat, freshwater mussels have evolved numerous ingenious methods to draw in their fish hosts. Some of these methods include flashy, moving mantle tissue displays mimicking prey items like minnows, crayfish, or eggs; releasing small packets of larvae called conglutinates that resemble tasty aquatic insects or worms; producing a mucus “net” containing glochidia to entangle hosts; putting their hosts in a “headlock” using teeth or ridges on the edges of their shells; and even fishing with a mucus “line” and a conglutinate lure. Mussel glochidia are tiny, usually not harmful to the host, and often only a few glochidia will successfully attach to an individual fish. The glochidia clamp onto the outside of the fish using their two valves and encyst for protection. The glochidia will then develop into a juvenile mussel resembling a miniature version of their parent after a few weeks to months. The now-juvenile mussel will drop off of the host fish, hopefully in a new, suitable habitat and burrow into the bottom. The tiny juvenile mussel will then spend the first months of its life using cilia (microscopic hair like structures) on its foot to collect food particles from the surrounding substrate and direct it into their shell to be digested. Once the juvenile has developed its adult filter feeding structures, it will move to the surface of the sand, mud, or gravel where it has been hiding and begin collecting suspended particles from the water column.

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some freshwater mussel host attraction strategies. A & B) Conglutinates, small bundles of mussel larvae which resemble invertebrate prey items. C & D) Mantle Lure, protrusions of pigmented mantle tissue which mimic prey fish (C) or invertebrates (D) and often move to attract predatory host fish. E) Superconglutinate, large bundles of mussel larvae which can resemble prey items and are often dangled like a fishing lure on mucus threads. F) Host Capture, some mussel species use tooth or ridge-like shell protrusions to temporarily capture and expose host fish to mussel larvae. Photo A, B, & F credit, M. C. Barnhart. Photo D credit Monte McGregor. Photo E credit, Noel M. Burkhead. Figure C, credit GA DNR Wildlife Resources Division.

filter feeding in the Ocmulgee River.

Photo by Georgia DNR

Wildlife Resources Division.

Freshwater mussels are a natural and vital part of Georgia’s aquatic ecosystems and carry out a variety of ecological functions that benefit our waterways. Some of these benefits include filtering suspended material—like algae and bacteria—out of the water column; oxygenating the streambed for small benthic creatures like burrowing insects and bacteria, providing habitat for other aquatic species; stabilizing fine sediments like silt and sand; acting as a food source for fish, birds, and mammals; and potentially, many more interactions that scientists have yet to discover.

Beyond their roles in the ecosystem, freshwater mussels also help humans to monitor the health of our waterways. Mussels are considered “indicator species,” meaning that their presence, abundance, and condition can be used by scientists as evidence of the health of an aquatic system. Mussels make good indicator species because they are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes and are often the “canary in the coal mine”, being among the first groups of animals to decline when habitats are damaged. Mussels are particularly sensitive to changes in flow patterns, erosion, sedimentation, water quality degradation, loss of habitat connectivity, and the impacts of invasive species. Another factor that makes them important indicators is their sedentary lifestyle. Unlike many species which can move to avoid changes to their habitat, stationary mussels must weather impacts to their habitat. Mussels are also long-lived, with many species living between 20 and 100 years! This means that the presence of mussels often indicates that conditions have not deteriorated beyond the mussel’s tolerances for a long period during its life. Their longevity and filter feeding behavior also allow mussels to bioaccumulate toxins from the water such as toxic metals, which can provide a picture of past and present water quality contamination.

filter feeding in the Ocmulgee River.

Photo by Georgia DNR

Wildlife Resources Division.

In addition to direct benefits provided by native freshwater mussels, it is important to recognize their intrinsic value. Mussels are part of the natural biodiversity of the world’s waterways and provide beauty, variety, and fascination to the people who enjoy Georgia’s natural resources.

Conservation of Freshwater Mussels

Unfortunately, freshwater mussels are one of the most imperiled groups of animals on earth, with over 70% of species being imperiled, threatened, endangered, or extinct. The cause for this concerning decline is primarily due to human alteration of the free-flowing river systems they depend on. The leading causes of mussel decline are dam construction, water withdrawal, flow alteration, water quality degradation, invasive species introductions, and climate change. Learn more about threats to Georgia’s aquatic biodiversity.

Freshwater Mussel Conservation Status in Georgia

Table: Number of species occurring in Georgia with federal or state listing status as Endangered or Threatened. All federally listed mussel species are also state listed in Georgia and are included in the values for state listed species. Information accurate as of November 2020.

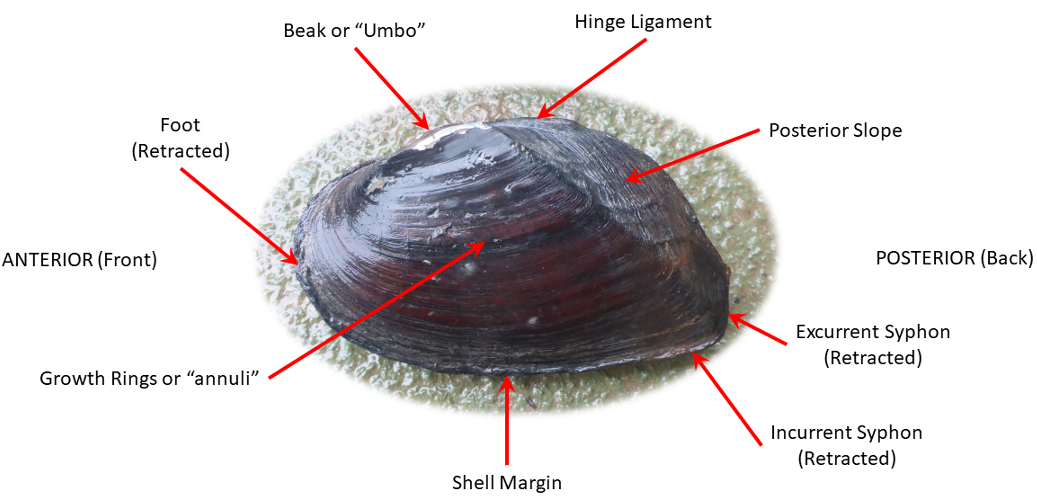

Freshwater Mussel Identification

Identification of freshwater mussels can be very difficult as variation within a species can be quite broad and the same species found in different locations can appear markedly different from one another. This problem is compounded by the fact that mussels do not have consistent, measurable characters like spines, scales, or body measurement ratios that can identify a species. Even under close examination, experienced biologists often have difficulty differentiating between some species. Some groups are even challenging to confirm using genetics! Freshwater mussel taxonomy is constantly changing as new evidence and new methods are brought to bear.

Unfortunately, no comprehensive resource is currently available to identify freshwater mussels in Georgia, however, the Georgia Biodiversity Portal provides species profiles, photographs, current conservation status, and range maps for Georgia mussel species of conservation concern as well as many other species of Georgia plants and animals. Some additional resources include several published books for specific portions of the state by prominent mussel biologists. Some of these books include: Freshwater Mussels of Florida, Freshwater Mussels of Alabama and the Mobile Basin, and Freshwater Mussels of Tennessee.

Native freshwater mussels are protected by state law, and many species are federally protected under the Endangered Species Act. Care should be used when handling mussels and live native mussels should not be collected for any reason.

More about mussels in Georgia

- Blog Post: Mussels: More Than Just A Shell in the Mud

- Blog Post: Study Spotlight: Mussel Mania in the Lower Flint River

- Blog Post: Mussels Go Fishing

- Blog Post: New Job Opens Eyes To Mussels

- Blog Post: Georgia’s Misunderstood Mollusks

- Video: Watch Out For Debris!: Mussel Research In Lake Jackson

Glossary of Terms

- Glochidia: The tiny, clam-shaped, parasitic larvae produced by native freshwater mussels.

- Host: A species of fish which can carry a glochidia until it metamorphosizes into a juvenile mussel. Mussel species often have specific host species and not any fish will do.

- Conglutinate: A small bundle of glochidia, often shaped like a food item to entice host fish into taking a bite and becoming infested. One female mussel produces numerous conglutinates.

- Superconglutinate: A large bundle of glochidia which often resembles a large prey item to entice host fish into taking a bite and becoming infested. One female mussel often only produces one superconglutinate at a time.

- Substrate: The river bottom, comprised of a combination of organic and inorganic material such as mud, silt, leaves, sand, gravel, cobble, boulder, and bedrock.

- Infaunal: An animal living within, as opposed to on top of, the substrate.

- Cilia: Tiny hair like projections that animals use to transport particles of food or generate flow by moving water.

- Juvenile: A mussel which has completed its metamorphosis from a glochidia larva into a miniature version of an adult.

- Bioaccumulate: The accumulation of toxins from the environment through absorption or feeding.

- Encyst: After a glochidia has attached to a host fish, the fish’s tissue encapsulates the glochidia to form a cyst as part of the fish’s normal immune response. This acts to protect the glochidia from the environment and avoid detachment.

Citations

- Williams, J. D. et al. (2014). Freshwater Mussels of Florida. University of Alabama Press.

- Williams, J. D. et al (2008). Freshwater Mussels of Alabama and the Mobile Basin. University of Alabama Press.

- Parmalee, P. W. and Bogan, A. E. (1998). Freshwater Mussels of Tennessee. University of Tennessee Press.