White-nose Syndrome in Georgia: 2024 Report

WNS in Georgia Caves

Additional Links:

Biologist Trina Morris speaks about WNS in Georgia

E-mail a question or report bats possibly affected

Help with winter WNS monitoring

WNS in North America

In winter 2006–2007, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation biologists began getting calls about bats flying erratically outside their hibernacula during the day. The bats were supposed to remain in the hibernation areas until spring and the insects that sustain them returned. But they were leaving the caves in extreme cold, and some were dying.

Inside, biologists discovered that clustered, hibernating bats had moved near the entrance instead of farther in, where temperatures are more stable. There were also scores of dead bats, and a strange white substance on the noses of some still alive.

Since, white-nose syndrome has killed millions of bats, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The main Georgia species that have suffered negative effects from the fungus included tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus), little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) and Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis).

WNS was first found in Georgia in February 2013. The cause of white-nose is a cold-loving fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The fungus was possibly introduced into a U.S. cave from Europe.

With the syndrome spreading rapidly, the Fish and Wildlife Service called in March 2009 for a voluntary moratorium on caving and other cave activities in WNS-affected and adjacent states. The service also advised cavers elsewhere to avoid using clothing and gear that had been used in those states.

In Georgia, the Wildlife Resources Division has developed a response plan and weighed options for managing access to caves and mines on state lands. Researchers have also limited scientific activities in caves.

“With white-nose syndrome confirmed at sites in Georgia, it is more important than ever that cavers follow decontamination protocols and reduce their trips to Georgia caves,” said Katrina Morris, a senior wildlife biologist with the Wildlife Resources Division. "We encourage all cavers and researchers to continue to take this issue very seriously."

More white-nose syndrome information, including advisories and updates on affected sites.

Please e-mail GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov:

- To report unusual bat die-offs or bats possibly suffering from white-nose. (Signs include white fungus on the muzzle, wings, ears or tail and bats flying outside during the day in temperatures at or below freezing.)

- Or, if you have questions about white-nose syndrome.

Please visit USGS's website to learn about submission guidelines.

White-Nose Response Plan

This Wildlife Resources Division plan outlines steps for raising awareness about white-nose syndrome, preventing or slowing its spread, reporting and analyzing bats, and managing related natural resources such as caves. The plan is flexible and will be updated as needed.

Questions? Contact Wildlife Resources at GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov or 706-557-3213.

Save Lucy: Campaign to Raise WNS Awareness Among Youth

The Save Lucy Campaign is a nonprofit organization created to raise awareness of white-nose syndrome and its impact on North American bats by engaging young people, providing conservation education to persons of all ages, and supporting research and other projects that protect bat populations threatened by WNS.

WNS FAQ

Much of this information is from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Other sources include the Georgia DNR’s Wildlife Resources Division and the U.S. Geological Survey.

- More info at whitenosesyndrome.org

- What is white-nose syndrome, or WNS?

White-nose syndrome is a malady blamed for the death of millions of bats in the U.S. WNS has been called “the most precipitous wildlife decline in the past century in North America.”

The disease is named for the white fungus on the muzzles and skin of affected bats. Discovered by a caver in eastern New York’s Schoharie County in February 2006 and documented by state biologists the following winter, white-nose has rapidly spread to sites throughout the Northeast and into the Southeast, the Midwest and Canada.

WNS is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd, which thrives in the cold and humid conditions characteristic of caves and mines used by bats.

Not all bats affected with WNS have obvious fungal growth, but they may display abnormal behavior (see below) in and outside of their hibernacula—caves and mines where bats hibernate during winter.

- How does it kill bats?

The fungus leads to bats being awakened too often from hibernation, or less intense periods of torpor. The bats may then use up fat reserves, which they need to survive hibernation, long before winter is over. Affected bats often leave their hibernacula during winter, searching for insects that have not yet emerged, leading to death of the bats by causes including starvation, cold and stressed immune systems.

Death rates of 90–100 percent have been seen in some hibernacula.

Emaciation and poor body condition were common factors in bat carcasses checked by the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center. Many of the bats examined had little or no body fat.

- How is WNS transmitted?

Bat-to-bat transmission has been verified and is considered the most common pathway. Affected sites generally following bat migration routes.

Research has also shown that viable Pseudogymnoascus destructans spores can be transmitted on gear, meaning white-nose may also be transmitted by people inadvertently carrying the causative agent from cave to cave on shoes, clothing and gear.

- Where has WNS been observed?

As of July 2025, white-nose has been documented in 40 states and nine Canadian provinces.

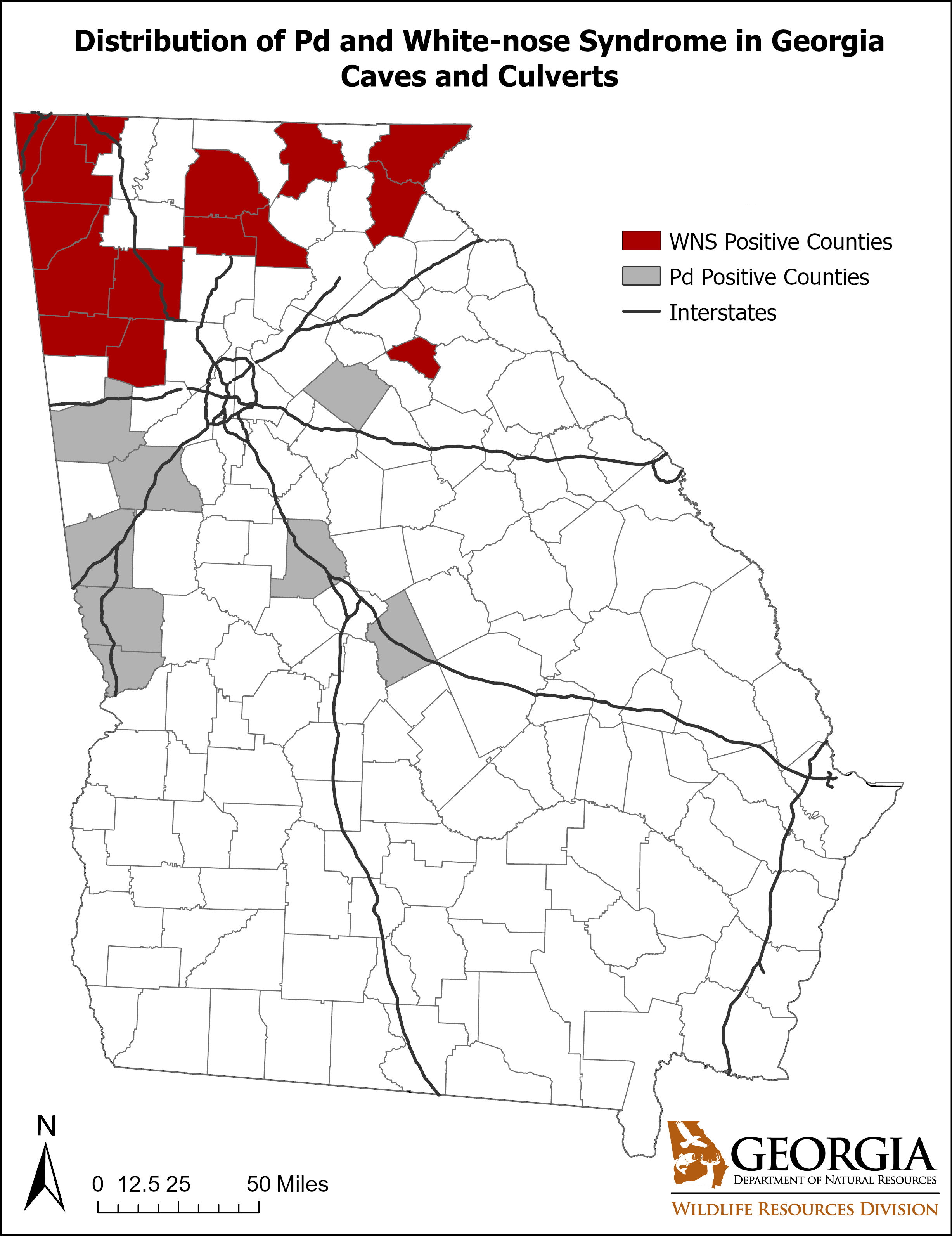

The syndrome was found at five Georgia sites—two in Dade, two in Walker County and one in Gilmer County—during cave surveys in February and March 2013. White-nose has since been confirmed or suspected in 14 counties. It also has been confirmed in four border states: Tennessee, Alabama and North and South Carolina.

- Does it affect humans or other wildlife?

There have been no reported effects on humans or other wildlife. However, authorities urge taking precautions and not exposing yourself unnecessarily to WNS. Scientists use protective clothing when entering caves or handling bats.

- What are the signs of WNS?

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, white-nose may be associated with some or all of the following unusual bat behaviors:

- White fungus, especially on the bat’s nose, but also on the wings, ears or tail.

- Bats flying outside during the day in temperatures at or below freezing.

- Bats clustered near the entrance of hibernacula.

- Dead or dying bats on the ground or on buildings, trees or other structures.

Hibernating bats may have white fungus that is not associated with WNS. If a bat with fungus is not in an affected area and has no other signs of WNS, it may not have white-nose.

- What is being done in Georgia?

Georgia’s Wildlife Resources Division has stepped up surveys to better assess bat populations, and limited scientific activities in caves. Researchers are also monitoring summer roost sites, which does not require entering caves, and working with other states and federal agencies.

The division has urged cavers and others to reduce trips to Georgia caves and follow national protocol for disinfecting clothes and gear. Wildlife Resources considered some closures—as advised by the Fish and Wildlife Service for WNS-affected and adjacent states—but chose voluntary limits after weighing research, the resource and public interests. This course of action will be reviewed and revised as needed.

Wildlife Resources has sought cavers’ help in spreading the word about white-nose and monitoring and evaluating caves on state lands. About 15 percent of Georgia’s caves are on state-managed lands.

The division has a WNS response plan. Designed to be simple and flexible, the plan outlines steps for raising awareness about the syndrome, preventing or slowing its spread, reporting and analyzing bats, and managing related natural resources such as caves. The document can help guide everyone from cavers cleaning their equipment to researchers scoring bat wing damage and animal control companies removing bats from a building.

- What are other wildlife agencies and organizations doing?

An extensive network of state and federal agencies, universities, caving grottos and private individuals are working to investigate the source, spread and cause of bat deaths associated with WNS, and to develop management strategies to minimize the impacts. The overall investigation has three primary focus areas: research, monitoring and management, and outreach.

Research topics vary from possible control measures to decontamination protocols, infection trials and sampling to determine how widespread the fungus is in the soil.

In addition, the U.S. Forest Service closed most caves and mines on Southeastern national forests in June 2009. Groups such as the Southeastern Cave Conservancy that own caves have closed or added permit requirements for some caves.

- What can I do?

- Reduce your trips to Georgia caves.

- Follow decontamination protocols.

- Help spread the word about WNS.

- Help with DNR surveys. (Contact DNR wildlife biologist Katrina Morris for details, GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov)

- What if I find dead or dying bats in winter or early spring, or observe bats with signs of WNS?

In Georgia, contact the Wildlife Resources Division at GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov or 706-557-3213.

It is important to determine the species of bat in case it is a federally protected species. If possible, photograph the potentially affected bats (including close-up shots) and send the photograph and a report to the Wildlife Resources Division.

If you need to dispose of a dead bat found on your property, pick it up with a plastic bag over your hand or use disposable gloves. Place the bat and the bag into another plastic bag, spray with disinfectant, close the bag securely, and dispose of it with your garbage. Thoroughly wash your hands and any clothing that comes into contact with the bat.

If you see a band on the wing or a small device with an antenna on the back of a bat (living or dead), contact the DNR Wildlife Resources Division (706-557-3213) or the nearest U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service office (the Southeast Region office is in Atlanta, 404-679-4000; www.fws.gov/southeast).

These band and transmitters are tools for biologists to identify individual bats.

- What should cavers know and do?

Georgia DNR encourages cavers to reduce their trips to caves on state-managed lands and follow U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocol for disinfecting clothes and gear. Cavers are asked to help spread the word about white-nose, and aid the Wildlife Resources Division in monitoring and evaluating caves on state lands.

The division encourages cavers to observe cave closures and related advisories involving other properties.

Cavers and cave visitors are also urged to stay out of caves in affected and in adjoining states to help slow the potential spread of WNS. Local and national cave groups have also posted information and cave advisories on their websites.

- What species of bats have been affected?

Here's a current list of species.

- What is white-nose syndrome, or WNS?

White-nose syndrome is a malady blamed for the death of millions of bats in the U.S. WNS has been called “the most precipitous wildlife decline in the past century in North America.”

The disease is named for the white fungus on the muzzles and skin of affected bats. Discovered by a caver in eastern New York’s Schoharie County in February 2006 and documented by state biologists the following winter, white-nose has rapidly spread to sites throughout the Northeast and into the Southeast, the Midwest and Canada.

WNS is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd, which thrives in the cold and humid conditions characteristic of caves and mines used by bats.

All bats affected with WNS do not have obvious fungal growth, but they may display abnormal behavior (see below) in and outside of their hibernacula—caves and mines where bats hibernate during winter.

- How does it kill bats?

The fungus leads to bats being awakened too often from hibernation, or less intense periods of torpor. The bats may then use up fat reserves, which they need to survive hibernation, long before winter is over. Affected bats often leave their hibernacula during winter, searching for insects that have not yet emerged, leading to death of the bats by causes including starvation, cold and stressed immune systems.

Death rates of 90–100 percent have been seen in some hibernacula.

Emaciation and poor body condition were common factors in bat carcasses checked by the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center. Many of the bats examined had little or no body fat.

- How is WNS transmitted?

Bat-to-bat transmission has been verified and is considered the most common pathway. Affected sites generally following bat migration routes.

Research has also shown that viable Pseudogymnoascus destructans spores can be transmitted on gear, meaning white-nose may also be transmitted by people inadvertently carrying the causative agent from cave to cave on shoes, clothing and gear.

- Where has WNS been observed?

As of June 2019, white-nose has been documented in 33 states and six Canadian provinces.

The syndrome was found at five Georgia sites—two in Dade, two in Walker County and one in Gilmer County—during cave surveys in February and March 2013. White-nose has since been confirmed or suspected in 14 counties. It also has been confirmed in four border states: Tennessee, Alabama and North and South Carolina.

- Does it affect humans or other wildlife?

There have been no reported effects on humans or other wildlife. However, authorities urge taking precautions and not exposing yourself unnecessarily to WNS. Scientists use protective clothing when entering caves or handling bats.

- What are the signs of WNS?

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, white-nose may be associated with some or all of the following unusual bat behaviors:

- White fungus, especially on the bat’s nose, but also on the wings, ears or tail.

- Bats flying outside during the day in temperatures at or below freezing.

- Bats clustered near the entrance of hibernacula.

- Dead or dying bats on the ground or on buildings, trees or other structures.

Hibernating bats may have white fungus that is not associated with WNS. If a bat with fungus is not in an affected area and has no other signs of WNS, it may not have white-nose.

- What is being done in Georgia?

Georgia’s Wildlife Resources Division has stepped up surveys to better assess bat populations, and limited scientific activities in caves. Researchers are also monitoring summer roost sites, which does not require entering caves, and working with other states and federal agencies.

The division has urged cavers and others to reduce trips to Georgia caves and follow national protocol for disinfecting clothes and gear. Wildlife Resources considered some closures—as advised by the Fish and Wildlife Service for WNS-affected and adjacent states—but chose voluntary limits after weighing research, the resource and public interests. This course of action will be reviewed and revised as needed.

Wildlife Resources has sought cavers’ help in spreading the word about white-nose and monitoring and evaluating caves on state lands. About 15 percent of Georgia’s caves are on state-managed lands.

The division has a WNS response plan. Designed to be simple and flexible, the plan outlines steps for raising awareness about the syndrome, preventing or slowing its spread, reporting and analyzing bats, and managing related natural resources such as caves. The document can help guide everyone from cavers cleaning their equipment to researchers scoring bat wing damage and animal control companies removing bats from a building.

- What are other wildlife agencies and organizations doing?

An extensive network of state and federal agencies, universities, caving grottos and private individuals are working to investigate the source, spread and cause of bat deaths associated with WNS, and to develop management strategies to minimize the impacts. The overall investigation has three primary focus areas: research, monitoring and management, and outreach.

Research topics vary from possible control measures to decontamination protocols, infection trials and sampling to determine how widespread the fungus is in the soil.

In addition, the U.S. Forest Service closed most caves and mines on Southeastern national forests in June 2009. Groups such as the Southeastern Cave Conservancy that own caves have closed or added permit requirements for some caves.

- What can I do?

- Reduce your trips to Georgia caves.

- Follow decontamination protocols!

- Help spread the word about WNS.

- Help with DNR surveys. (Contact DNR wildlife biologist Katrina Morris for details, GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov)

- What if I find dead or dying bats in winter or early spring, or observe bats with signs of WNS?

In Georgia, contact the Wildlife Resources Division at GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov or 706-557-3213.

It is important to determine the species of bat in case it is a federally protected species. If possible, photograph the potentially affected bats (including close-up shots) and send the photograph and a report to the Wildlife Resources Division.

If you need to dispose of a dead bat found on your property, pick it up with a plastic bag over your hand or use disposable gloves. Place the bat and the bag into another plastic bag, spray with disinfectant, close the bag securely, and dispose of it with your garbage. Thoroughly wash your hands and any clothing that comes into contact with the bat.

If you see a band on the wing or a small device with an antenna on the back of a bat (living or dead), contact the DNR Wildlife Resources Division (706-557-3213) or the nearest U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service office (the Southeast Region office is in Atlanta, 404-679-4000; www.fws.gov/southeast).

These band and transmitters are tools for biologists to identify individual bats.

- What should cavers know and do?

Georgia DNR encourages cavers to reduce their trips to caves on state-managed lands and follow U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocol for disinfecting clothes and gear. Cavers are asked to help spread the word about white-nose, and aid the Wildlife Resources Division in monitoring and evaluating caves on state lands.

The division encourages cavers to observe cave closures and related advisories involving other properties.

Cavers and cave visitors are also urged to stay out of caves in affected and in adjoining states to help slow the potential spread of WNS. Local and national cave groups have also posted information and cave advisories on their websites.

- What species of bats have been affected?

Here's a current list of species.

- What is the impact on bat populations?

By Fish and Wildlife Service estimates, millions of bats have died from WNS, and there seems to be no end in sight. Bat mortality rates of 90-100 percent have been reported at some hibernacula. There may be differences in mortality by site and by species within sites. The average decline in bats counted during surveys at Georgia sites monitored since at least 2013 is more than 90 percent.

What is the impact on the environment?The impact is unknown. But, bats play a critical role in the health of natural habitats: They are the major predator of night-flying insects, eating on average half their weight in insects in a night, including agricultural pests. (One analysis estimated that the pest-control services provided by insect-eating bats save the U.S. agricultural industry at least $3 billion a year.) Bats also provide nutrients vital to some cave habitats.

In the tropics, bats that eat fruit and nectar help pollinate plants and disperse seeds.

Many bat populations are already in decline because of habitat loss. Their ability to rebound is limited by reproduction rates as low as one offspring a year.

WNS Winter Monitoring and Surveillance

We are urging cavers and others in the outdoors to be on the lookout for bats infected with white-nose syndrome (WNS) this winter. Follow the instructions below to help the Georgia DNR with WNS monitoring and surveillance.

What to Report

It is not unusual to see bats flying during the winter months. They may emerge during warmer periods at night to eat, drink or just stretch their wings. However, bats infected with WNS have been seen flying outside during the day during very cold periods in the winter. You may also find dead bats on the landscape that are infected with WNS. Signs of WNS include white, fuzzy growth on the muzzle and wings and possible deterioration of the wing membranes.

If you see unusual bats on the landscape or have a WNS-suspect bat to send in for testing, please report it by sending an e-mail to GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov.

If you collect WNS suspect bats, always use gloves and place bats in double ziploc bags. Put the bat in the refrigerator as soon as possible and follow the instructions on the USGS's website for submission to the lab for testing.

Information for Cavers

We need your help! If you have received sampling kits, please follow the instructions below when visiting caves.

If you are visiting caves in Georgia and you have not received swabs for sampling, we would still like you to submit information to Georgia DNR.* We are collecting data on caves with and without bats. Below are links to a field form for WNS monitoring, an Excel file for submitting monitoring data and an instruction sheet.

And remember, if you are visiting caves, please follow clean caving protocols! Help protect Georgia’s bats.

WNS Education Information

Georgia DNR and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have developed some education materials for WNS. If you are interested in any educational information or if you would like to request a WNS presentation from DNR for your grotto or group, please e-mail GADNRBats@dnr.ga.gov.

*Such data submitted to Georgia DNR is not subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. The Wildlife Conservation Section of DNR is responsible for protecting sensitive data and any cave location data submitted will be treated accordingly